Group decision-making: How to do it right

Introduction

Group decision-making is a collaborative process in which people come together to make a decision, usually by consensus. The decision may be one-off, or the group may create a tool or framework to help make consistent decisions repeatedly.

Decisions made by groups have better buy-in, and can leverage the diverse perspectives, experiences, and skills of the group. However, despite these and other advantages that it has over individual decision-making, group decision-making also comes with its own challenges. In this article, we’ll give you an ultimate guide to the group decision-making process and examples of group decision making techniques, along with insights into group decision making psychology from behavioral science – so you know exactly what to look out for and how to make the most effective decisions with your team.

When to use group decision-making

Group decision-making can be used anytime there is a decision to be made that affects multiple stakeholders. Some examples include creating government policies, deciding which candidate to hire for a job, judging competitions, managing company projects, or even something as relatively low-level as deciding where to eat with your friends.

At a higher level, group decision-making techniques can be used to capture leadership judgements, build consensus as a group of stakeholders, codify expert judgment to create decision-making tools, improve consistency in important decisions, and increase participant understanding through group discussions as part of the decision-making process.

Especially for high-stakes decisions, such as company investments or new public policies, making decisions with a group of experts rather than as a single individual allows you to make much more effective decisions and significantly reduces risk.

However, in situations where you are very pressed for time, individual decision-making may be a better option as it can require a lot more time to come to consensus as a group. Individual decision-making may also be the better way to go for simpler or more personal decision-making situations.

Advantages of group decision-making

As with anything, group decision-making comes with its strengths and weaknesses. Here we will discuss some of the advantages of group decision-making, as well as some of the drawbacks and some tips on how to mitigate them.

Gaining deeper insights into the issue

Group decision-making can be a powerful tool for making important decisions. Including the input of people from diverse backgrounds helps you cover all aspects of the issue at hand, and include information you may not have been aware of in your decision. This helps you make more optimal decisions than you would otherwise be able to make alone.

Usually, it is impossible to know everything that there is to know about any given decision. In some cases, being unaware of certain information can actually cause us to make choices that are contradictory to our goal. Group decision-making helps you avoid such pitfalls, by including insight from people who can share their knowledge and perspectives with you.

In addition to helping to keep you more informed in decisions, group decision-making can help you include the insights of subject matter experts. This is especially useful in complex situations where you may want to include experts from different subjects, such as in procuring health technologies and pharmaceuticals, where clinicians, administrators, patients and economists can all make valuable contributions.

Increasing acceptance of the solution

Group decision-making can increase acceptance and buy-in from stakeholders (for example, in public policy creation) by having a group of decision-makers present that is representative of the stakeholders. Individuals are more likely to feel heard when various perspectives are included in the decision, and therefore trust the decision-making process more.

Reducing personal biases

Another big advantage of group decision-making is its ability to reduce the risk of individual cognitive biases in your decision. Since it takes a long time to study a problem in great detail, humans have evolved mental shortcuts, also known as heuristics, that allow us to make decisions very quickly. However, although these shortcuts can be very helpful, they may also lead to biases. Further biases can stem from our desire to protect our ego, including only paying attention to information that confirms our beliefs, or being more critical of others than of ourselves. If we include several individuals in our decision-making group, then we are more likely to reduce the impact of our individual biases and reach a more optimal decision.

Disadvantages of group decision-making

Despite the clear advantages of collaborative decision-making, there are some potential pitfalls to manage: it is likely to take longer to reach a decision, and groups are prone to some interesting biases.

Time required to decide on a solution

Arguably the most obvious disadvantage of group decision-making is that it is more complex to manage the group decision-making process than to make decisions alone. In turn, it also usually requires more time to reach a decision as a group than as an individual, which may be suboptimal in situations that require quick action. Because of this, group decision-making might not be ideal in a situation where the decision needs to be made very quickly. Clear direction, a mandate from senior leadership, and an experienced facilitator can help keep your group decision-making project on track.

Group decision-making biases

Although group decision-making helps mitigate individual biased heuristics, it can lead to other biases, according to studies in group decision-making psychology. One of the most studied group biases is groupthink, a phenomenon that discourages individuals from giving dissenting opinions, due to our inherent social desire to conform to the group. This discourages creative thinking, and in extreme circumstances can lead to the people involved ignoring ethical consequences of the decision, in favor of achieving the goal.

Group decision-making is also subject to the group polarization phenomenon, where groups are more likely to make extreme decisions than individuals. This can be detrimental in situations where there is risk involved, such as adventure sports, where a group of adventurers may be more likely to take a risk after group discussion than they individually would be before discussions, as the tolerance for risk shifts more towards the extreme end.

Some of these issues inherent in group decision-making can be mitigated by 1000minds decision-making software. The built-in PAPRIKA algorithm elicits decision-maker preferences by breaking down the problem into a series of smaller choices where each individual decision-maker is asked to anonymously vote on their preferences. This gives stakeholders a way to provide their input without having to worry about conforming to the group (groupthink), and the process encourages discussion until consensus is reached. Schedule a call with a 1000minds expert to learn how to use the software for your group decision-making needs.

Group decision-making process

A thorough and reliable group decision-making process can be summarized through the following steps:

1. Structure the problem

Clarify all aspects of the issue at hand. What is the problem that you are trying to solve? Who are the stakeholders involved? Who are the decision-makers? Which group decision-making techniques are appropriate for this situation?

Undoubtedly, one of the trickiest but most important aspects of structuring the problem is defining the overarching question. For example, when prioritizing company projects to develop, the overarching question might be “which projects would bring in the most revenue?”, or it might be “which projects are most aligned with our strategic plan?” Defining the overarching question in specific terms helps contextualize the decision-making problem and align your approach for subsequent steps of the decision-making process more closely with your goal. Otherwise, in terms of project prioritization, people might just prioritize projects based on personal preferences; rather than, say, company objectives.

2. Identify alternatives

Determine a list of possible solutions, or alternatives, for the problem. Depending on the application, you may already have a list of alternatives at hand, or you may have to come up with new alternatives as a group.

In some situations, your objective may not be to find a specific solution for an immediate one-off decision, but rather to create a tool for future or ongoing repeated decision-making applications. This could be applicable for developing a framework for prioritizing patients for hospital treatment, or creating a scoring mechanism for rating the biodiversity of gardens. While you can skip this step in those cases, making up ~10 alternatives regardless can be helpful for thinking about your criteria, as discussed in the next step. If using 1000minds decision-making software, our AI assistant can help generate alternatives for you.

3. Specify criteria

Identify the criteria and corresponding levels that are relevant to the solution. For example, for updating your energy infrastructure, some relevant criteria may be how environmentally friendly the solution is, how much energy it can produce, how cost-effective it is, and what the initial installation costs are.

In 1000minds decision-making, your costs, risks, and other considerations are generally kept separate from your criteria. This allows you to use a “value-for-money” chart to compare the alternative scores against these costs and considerations, and thereby find which alternative has the best value-for-money – rather than just the highest score.

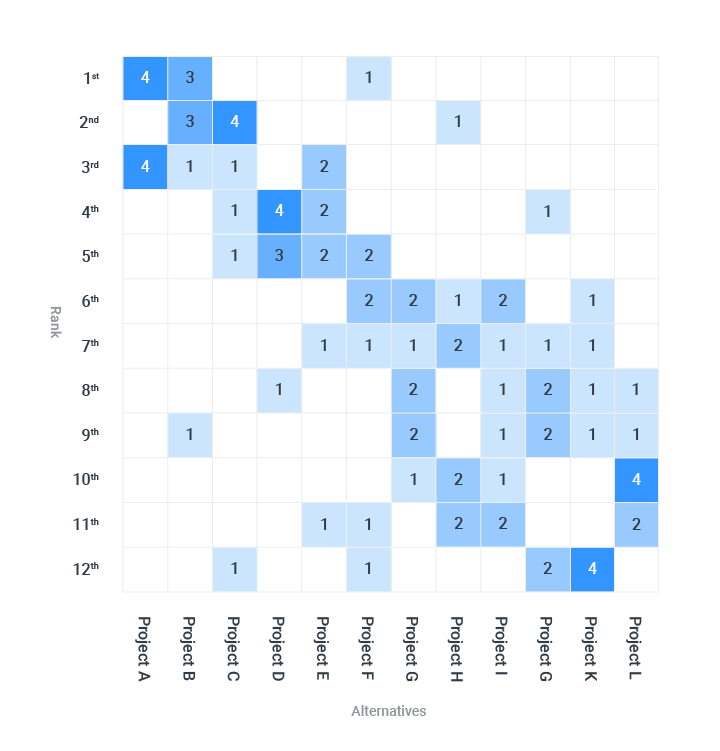

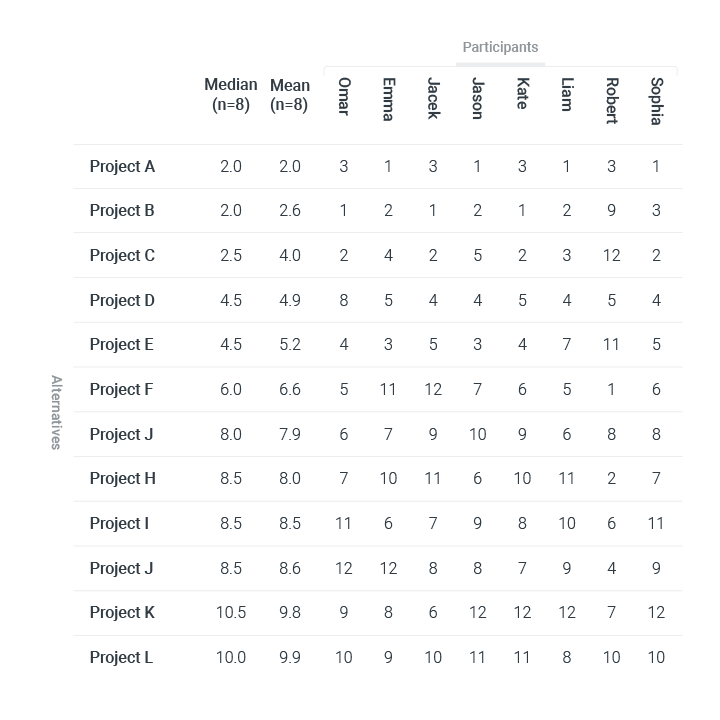

Identifying possible alternatives (as in step 2) before identifying criteria can help you think about what criteria are relevant when comparing the alternatives. A 1000minds ranking survey – also known as a “noise audit” – can be used to gather your group members’ individual rankings of the alternatives, and demonstrate the variability of their judgments on alternative rankings, as in Table 1 & Table 2 below. This shows the need for a more structured decision-making process, and promotes discussion about relevant criteria: “Why did you rank A ahead of B?”.

4. Rate the alternatives on the criteria

After specifying your criteria and possible alternatives, discuss as a group how you believe the alternatives perform on the criteria. Some of these might be numerical intervals that you can gather through research – for example, the average temperature of a city’s climate – while others may be more qualitative in nature and subject to personal judgment. A 1000minds categorization survey helps you gather each participant’s input about these alternative categorizations, with the option of keeping responses anonymous.

5. Measure relative importance of criteria

Once you have established your criteria, you need to figure out the relative importance, or weights, of your criteria. Which criteria matter most when deciding on a solution for your problem, and by how much? Which criteria are less important?

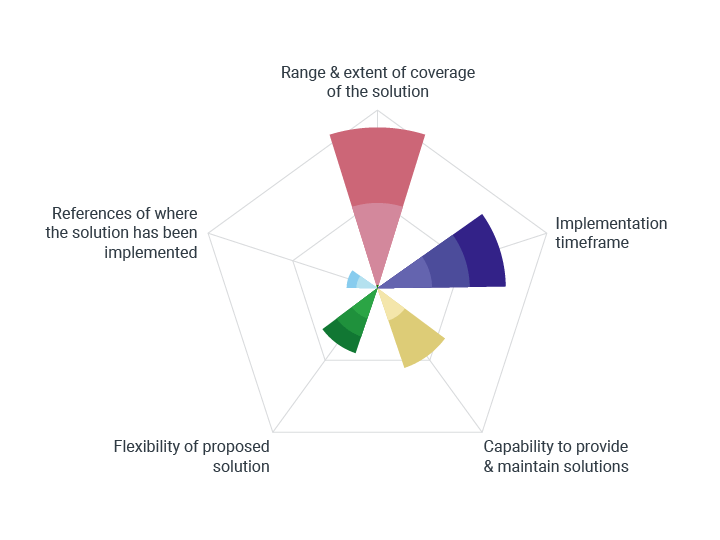

To find the relative importance of your criteria, you can use one of the decision-making techniques below to come to an agreement with your group about how to weigh or rank your criteria. For important decisions, we recommend using group decision-making software such as 1000minds, which generates reliable criterion weights based on your answers to questions that are carefully formulated to elicit decision-makers’ preferences and judgements. Decision-making software has more scientific validity than other decision-making methods.

6. Evaluate and rank alternatives

The weights of the criteria found in step 5, and the alternative categorizations determined in step 4, allow you to rank your alternatives according to these scores.

If you have followed the recommendation to keep cost separate from your criteria, you can plot alternatives on a graph with scores on the y-axis, and cost on the x-axis. This lets you see the value for money of the alternatives, with a higher y/x ratio representing a greater value for money, or a bigger “bang for buck”.

7. Implement your solution

The last step is to discuss our findings, including any significant limitations of the analysis, and then implement the appropriate solution. For higher-level decisions, it’s important to also allow for uncertainty and to check the robustness of your data and results, and you can use graphs and charts provided by decision-making software such as 1000minds to communicate findings with stakeholders. These results can be used to support decision-makers in reaching and, if need be, defending their decision.

Keep in mind that this decision-making process is not necessarily linear – you might go back and forth between different steps as new information is uncovered or as the decision-making process reveals a need to reword or restructure some components of the decision.

Group decision-making examples

Group decision-making can be applicable to many situations. A few examples may be:

- Allocating funding for projects

- Hiring a new employee

- Designing governmental policies

- Planning where to spend your vacation with your friends

Depending on the complexity or circumstances of the situation, you might use different group decision-making techniques. Brainstorming might be adequate and the most convenient for choosing a vacation destination with friends, whereas designing a governmental policy requires a much more thorough decision-making technique.

Below, we’ll apply the decision-making process discussed earlier to a higher-level decision situation: shortlisting proposals received in response to an RFP (Request for Proposal) as part of a tender process.

Step-by-step group decision-making example

Let’s say that you work at a large company that is trying to shortlist proposals received during a tender process. Working with a team of decision-makers, perhaps a group of 6, would help you make a better decision about which proposal to accept. After you’ve established the group that would be making this decision, you can begin with the group decision-making process outlined above.

1. Structure the problem

First, describe the problem at hand: what does this decision entail? What are the desired outcomes of this decision? Make a list of these goals so you can keep them firmly in mind. Having a diverse group of decision-makers and experts can help you cover all aspects of the problem.

As mentioned earlier, be specific with the overarching question that guides the decision-making process. Rather than phrasing the question vaguely as “which proposal should we select?”, you could say instead “which proposal best meets the needs and requirements of the organization?” to contextualize the problem.

2. Identify alternatives

For this particular example, you probably don’t have any alternatives yet since it would be better to define your criteria and weights before going out to tender, so that your criteria are not influenced by any particular proposals. In such a case, create some fictitious alternatives, or perhaps use some proposals from a past project as your alternatives for the sake of drafting criteria. Write a short description of each proposal as well. If using 1000minds decision-making software, our AI assistant can generate alternatives and descriptions for you.

3. Specify criteria

Use one of the group decision-making techniques mentioned later in the article to discuss how you would compare or rank the alternatives identified above. You can use a 1000minds ranking survey here. Keep in mind that the rankings created in this step won’t be the final alternative rankings; the purpose of this process is to prompt group participants to think about why they choose to rank some alternatives higher or lower than others.

From this, your group can identify a list of criteria – things that matter to you about the proposal or the contractor that submitted it. You can use brainstorming, the nominal group technique, or the delphi method to come up with these criteria.

Your list of criteria might look like this:

- Cost

- Capability to provide & maintain solutions

- Implementation timeframe

- Range & extent of coverage of the solution

- References & case studies of where the solution has been successfully implemented

- Flexibility of proposed solution

- Financial risk

- Special strategic considerations

Next, you will have to decide on different levels for these criteria, which can be either qualitative (“low”, “medium”, “high”) or quantitative (“Less than $1 million”, “$1‑2 million”, “$2‑5 million”, etc). Wherever possible, it is best to have explicit levels – e.g. for the implementation time frame criterion, one level may be “6-12 months”, rather than “short” – so that your decision-makers are all on the same page and it is easier to visualize and therefore think about the levels.

As mentioned earlier, we recommend keeping costs and other considerations separate from other criteria, so you can weigh alternative scores against your costs to determine which alternative would give you the best value for money. In this case, let’s classify “cost”, “financial risk”, and “special strategic considerations” as other considerations, rather than criteria.

4. Rate the alternatives on the criteria

Gather data about how your alternatives perform on the criteria. For criteria where no measurable values are available – for example, “capability to provide & maintain solutions” – discuss with your group how you would categorize, or rate, the alternatives with regard to those criteria. A 1000minds categorization survey can be helpful to gather your group’s judgements here.

5. Measure relative importance of criteria

There are a variety of ways in which you can determine the relative importance of criteria. You can use the pairwise comparison method, pairwise voting, or specialized group decision-making software. For a high-stakes decision such as this, we recommend using decision-making software with group decision-making capabilities, to ensure that your decision is scientifically valid and reliable, and to minimize the group decision-making biases mentioned above. This will also help you determine numerical weights of the levels of your criteria.

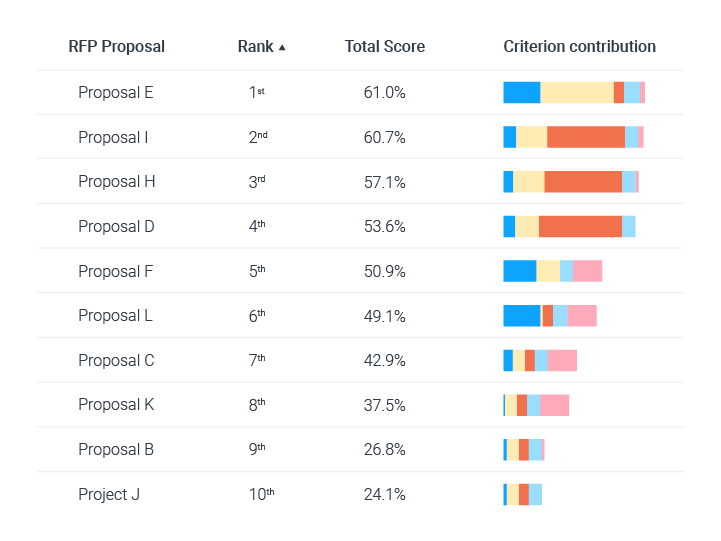

6. Evaluate and rank alternatives

Score your alternatives – typically in the range 0-100% – based on the relative importance of the criteria and levels discovered in the previous step. Rank your alternatives from highest to lowest based on those total scores. Group decision-making software will perform this step automatically for you.

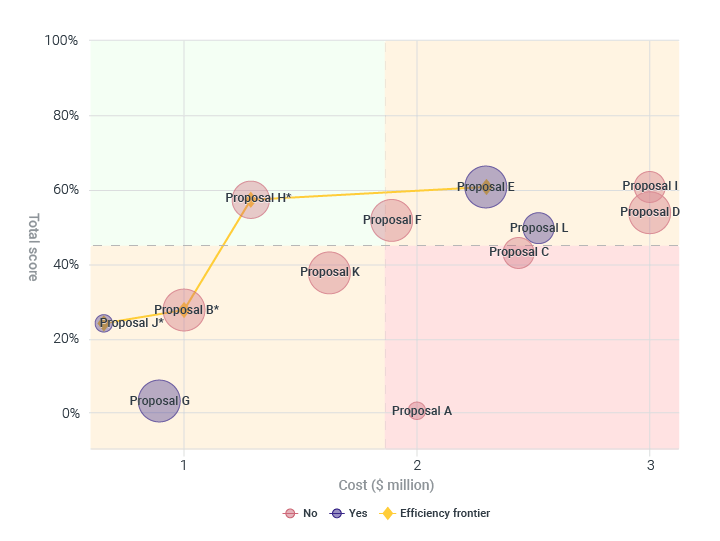

Because we kept our costs and other considerations separately, we can now make a value-for-money chart based on the alternative scores. We can do this by plotting “score” on the y-axis and “cost” on the x-axis. Additional considerations, such as “financial risk” and “special strategic considerations”, can be displayed on the chart by using different bubble sizes and colors, as in Figure 2 below.

This chart can be used to support a discussion among the group of decision-makers about which alternative delivers the best value for money, or the biggest "bang for buck". This would be any alternative on the efficiency frontier (on the yellow line), or the alternative with the highest score:cost ratio. The bubble sizes and colors also help us consider the financial risk involved, and whether there are any strategic considerations.

Based on these factors, proposal H looks like the best solution. Although proposal E has the highest score, it also has a much larger cost than Proposal H, and higher risk associated with it, so proposal H seems to be the better choice.

7. Implement your solution

Our analysis and results can be used to communicate and explain the final decision to stakeholders. Additionally, as for any analysis based on uncertain inputs, we can perform sensitivity analysis to check the robustness of the results to plausible variations in the alternatives’ performances (step 4) and their scores on the criteria levels and the criteria weights (step 5).

Group decision-making techniques

There are various group decision-making techniques that can be used to carry out and facilitate some of the fundamental steps discussed above. Some may be more appropriate than others depending on the situation at hand. Here are a few commonly used group decision-making techniques. Note that these methods are not necessarily mutually exclusive – some can be combined, e.g. brainstorming + nominal group technique + Delphi method + group decision-making software.

Group decision-making software

Decision-making software is the most scientifically valid and reliable method for making effective decisions. It helps you evaluate your alternatives in a logical, data-driven manner, as well as provide visuals and other methods to share your analytical insights with stakeholders.

1000minds decision-making software breaks down complex decisions into smaller components, allowing businesses to tackle each individual aspect of the decision. It works by eliciting the decision-makers’ or experts’ judgments about the relative importance of each criterion through a series of questions that require the decision-maker to make a trade-off. 1000minds’ group decision-making software incorporates a voting mechanism into this process, which encourages discussion within the group until consensus is reached. On the other hand, if decision-makers are unable to participate in the voting and discussion process together at the same time, 1000minds also offers preferences surveys that each individual can complete on their own time (without discussion). Both voting and preferences surveys can be done completely anonymously, ensuring that every individual can provide their input without worrying about backlash from the group or otherwise being subject to group biases. , ensuring that every individual can provide their input without worrying about backlash from the group or otherwise being subject to group biases.

The decision-makers’ preferences that are elicited in this way are used to determine numeric weights, or preference values, for each criterion and its levels. These values are then applied to the alternatives entered, which are scored according to the preference values. Alternative scores can be plotted on a chart to measure against costs or risks involved, allowing you to choose the best “value-for-money” while having data to back your decisions.

Brainstorming

Brainstorming can be a good way to generate a variety of criteria or alternatives that may be relevant to the decision at hand. In brainstorming, the moderator describes the problem in detail so as to give each decision-maker a complete picture of the issue. Then, decision-makers can either brainstorm ideas individually on a piece of paper and share with the group afterwards, or brainstorm together as a group and write ideas on a flipchart as they come up.

A disadvantage of brainstorming is that individuals may be hesitant to share their ideas, for fear of judgment or criticism by the rest of the group. To overcome this problem, ideas can be collected and shared anonymously. In addition, brainstorming does not offer a way to evaluate and decide on alternatives.

An AI assistant can be a highly useful tool for brainstorming. By entering a clear prompt describing your decision-making objective and asking for a list of suggestions, AI can provide astonishingly helpful ideas. However, some AI outputs can be inaccurate or strange, so decision-makers should use care when generating ideas via AI. 1000minds offers a built-in AI assistant that generates criteria and alternatives for you, while following a human-in-the-loop approach to keep you in the driver’s seat at every step.

Nominal group technique

The nominal group technique is a great way for generating a higher quality list of alternatives than brainstorming allows, and for encouraging equal participation of all group members when group dynamics are imbalanced.

First, the moderator presents the decision problem to the group. Each individual is then asked to list their ideas for solutions on a piece of paper in brief sentences, working silently and independently. After some time has passed and individuals have had enough time to think of ideas, the moderator asks each individual to share an idea one-by-one. At this point, no criticism or comments are allowed, in order to encourage participants to share their ideas freely.

After a sufficient number of ideas has been recorded, the moderator goes through each idea to ask if anyone has any question about an idea or needs something to be clarified. Once every idea has been clarified, each idea is discussed in turn. To score and rank alternatives, each individual then writes down their ranking of the solutions on a piece of paper, with preferred solutions receiving a higher score. The papers are then collected, and the votes are tallied on the flipchart, resulting in a ranking of the alternatives that represents the overall preferences of the group. Alternatively, the nominal group technique can be used solely for the purpose of generating and discussing a list of alternatives, while another technique – such as decision-making software – can be used for scoring and ranking these alternatives.

Dialectical inquiry

Dialectical inquiry is a group decision-making technique that aims to uncover all the relevant information about each alternative through debate. Dialectical inquiry works by dividing the group of decision-makers into two opposing sides to debate the advantages and disadvantages of each alternative one by one. This goes on until consensus is reached about which alternative offers the best solution. Because of the amount of discussion required to evaluate each alternative, dialectical inquiry is best suited for situations where few alternatives are present.

Delphi method

The Delphi method (named after the Oracle of Delphi) is a group decision-making method that is designed to gather the opinions of experts from a variety of fields and reduce group decision-making biases. It works by designating a moderator, who sends a carefully designed questionnaire to the experts. The experts answer the questions individually in their own time, and send back the completed questionnaire to the facilitator. The answers are then combined and presented in subsequent questionnaires, so that each expert can review the input gathered from the others, and answer the next questionnaire according to this input and their potentially modified judgment.

The advantage of the Delphi method is that it helps build consensus among experts, while gathering their input anonymously and thereby reducing group biases. However, the Delphi method requires more time to reach a decision, and therefore may not be suitable when decisions need to be made quickly. 1000minds surveys can be used to streamline a Delphi process. To learn more, see our ultimate guide to the Delphi method.

Possibility ranking

Possibility ranking works by voting on alternatives or creating a list of ranked alternatives as a team. The advantage of this method is that it can be used remotely and anonymously; however, it does not create much room for discussion.

In possibility ranking, group members are asked to rank alternatives according to their judgment. These rankings are then collated, and alternatives are prioritized according to the average rankings.

Tips and strategies for better group decision-making

Group decision-making can get complicated and lead to sub-optimal results if not done correctly. Here are a few group decision-making strategies that can help you manage the process more effectively.

Include a diverse group of decision-makers

It is important that you include a diverse group of people in your decision-making group, in order to be able to view the problem from different perspectives and gain a deeper understanding of the situation at hand. Furthermore, including a diverse group helps mitigate the polarization phenomenon that might occur if most of your participants have similar views, and therefore you’re less likely to make extreme or more risky decisions.

Gather opinions anonymously

In order to counter people’s hesitance to speak up for fear of judgment from the group, it is important to protect their anonymity. This can be done by having group members contribute ideas anonymously on a shared document, or use anonymous voting to decide between alternatives. 1000minds decision-making offers anonymous voting as part of the trade-offs process to elicit relative importance of the criteria.

Be mindful of group size

Group decision-making can be done with anywhere from 2 to 10+ decision-makers. However, with larger group sizes, it becomes more difficult to effectively manage discussion and group dynamics. Some studies suggest the ideal group size for decision-making to be around 5-7 participants. One way to increase this limit is by using group decision-making software, which can help mitigate the aforementioned issues that arise from group dynamics. Alternatively, 1000minds preferences surveys can be used to gather preferences from a wider group of people to be used for decision-making, allowing you to include up to 5000 participants.

Try 1000minds

Group decision-making can be tough, but with the right methods, you can minimize any drawbacks and achieve optimal outcomes. If you want to take your group decision-making to the next level, try out 1000minds’ group decision-making software by signing up for a free 15-day trial. Choose one of our dozens of examples to get started, use our AI assistant to generate ideas, or build your own model from scratch!